Proud to Be Pell

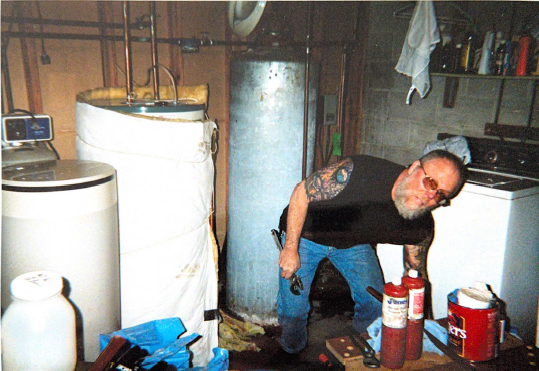

My grandpa spent his career as a plumber. Once, long before the pandemic gave new meaning to the term “essential,” he was sent home as an “inessential worker” (during some financial crisis or another). “Essential?” he used to say. “I’m pretty damn essential when s**t starts flowing down the hallway.” He retired, took incredible care of himself, and then died quite suddenly before he reached 70. My family blames Vietnam. Me? I blame the s**t.

I think he would have liked Columbia, though he was never particularly convinced about the necessity of college. At the very least, my experience here certainly would have surprised him. I’m a Pell Grant student here, one of the 16% of Columbians with enough “significant financial need” to receive government grant money. In reality, most of my financial aid comes from the University, but it can be a helpful category. Pell Grant recipients embody a vast range of identities and experiences spanning the lower middle class, the working class, and those living below the poverty line. Some of us are queer, POC, or first generation. I became an Inclusion and Belonging ambassador here at Columbia because socioeconomic status tends to be an overlooked identity that not only provides complexity to these others, but that also has an important social context of its own.

It’s easy to make the case that low income students like me make Columbia a better place. We have personally experienced many of the social, cultural, and financial problems that good-hearted Columbians strive to solve; in a way, it gives us a sort of practical edge. Even so, it’s not easy to be low income here. In my mind, Pell Grant students at Columbia face five major barriers to our sense of belonging within the community.

False Conclusions. Poverty is not an embarrassment. Poverty is both a situation and a part of someone’s identity that reflects less on them individually, and more on a system that allows some to live without a sense of shame about their financial status. It makes one wonder: “Why are we whispering?"

Anonymity. My grandmother worked at a laundromat for roughly twenty-three years. She washed and folded people’s dress shirts, their socks, their underwear. At night, she’d walk home with a roll of quarters in each hand, ready to defend herself so she could make it safely back home to her twins. If something had happened to her on one of those walks home, it’s unlikely that the people whose dress shirts, socks, and underwear she washed would have recognized the name Barbara Walsh on a “missing” poster. This anonymity is the first barrier to a sense of belonging for many, and those who live in poverty are no exception.

Assumed Exclusivity. My freshman year, I went back to my high school over winter break and helped hand out Columbia brochures to the students there. Washington High is very friendly, and we had a big crowd around the table. I only heard one of three things from the students who approached us. One: “I’m too stupid.” Two: “I’m too poor.” Three: “My parents don’t want me to go to college.” The final barrier is entirely practical.

None of the kids I talked to that day were stupid, not a single one. My take? They believe they are stupid because they know they are poor. Let’s see: I am smart. Smart people go to Columbia (or Harvard or Yale). Nobody like me goes to Columbia (or Princeton or Brown). I must not be smart. We'd love to think this is just the mad logic of imposter syndrome, but it stems from a much deeper problem; as long as elite universities fail to acclimate and make visible their communities' low income students, poor and working class kids will continue to receive the message that their own education is a rigged game leading toward a dead end.

Financial Secrecy. While the privacy of one’s financial affairs is anything but a barrier to success, there is an important - but often overlooked - distinction between privacy and secrecy. When the Columbia Student Council publishes the amount of money spent providing low income students with winter coats, the recipients’ identities may be kept private but their collective financial footprint is not.

The Constant Recipient. Once you see yourself as a recipient, your identity can feel like the sum of a constant series of transactions. Every financial splurge, every lucky childhood experience, every moment when I can afford something, I am plagued with the vision of all of those who are not awarded the same luxury--some being my friends and family. I think this is a problem many Pell recipients have; we embody a wide range, and we lack the type of collective spirit that instills pride in the importance of our varied experiences. And, when we are mentioned in a newsletter or a pamphlet, all too often, it’s about what we get from this community, never what we give.

Once you see yourself as a recipient, your identity can feel like the sum of a constant series of transactions...And, when we are mentioned in a newsletter or a pamphlet, all too often, it’s about what we get from this community, never what we give.

Here’s what I’ve got to say in response to each of these barriers:

False Conclusions: Low income students: You desire an education that you have to get the hard way. My guess is that you have encountered more than a few challenging situations along your journey. But, low income students: what you bring to the table is essential and valuable. The stories you have in your back pocket don't go away, but there are no empty parts of you. You lack nothing in the way of intelligence, bravery, and beauty.

Anonymity: Low income students: you are not embarrassing, and you are anything but anonymous. Your families are powerful, the foundation that supports this world. When you succeed, you are more than an “unlikely” success story, despite the weight you may carry on your shoulders. When you fail, you have not fallen as far as it seems; that’s only the extra weight you’re feeling, which pushes more on a step down than on the walk up.

Low income students: you are more essential to Columbia than the money you receive, more valuable than the money you spend. You give a lot, including your all.

Assumed Exclusivity: Low income students (and Washington High Warriors): Columbia is lucky to have you (or would be lucky to have you). Columbia wants you here. There is no barrier you cannot surpass, and you don’t have to do it silently. And, to those Columbians who may not have family in these professions: have reverence for the plumbers (and the custodians, the trash collectors, the food service workers) because without them, your dreams and ambitions would sputter and fall apart in a mess of your own s**t as it flowed down the hallway.

The Constant Recipient: Low income students: you are more essential to Columbia than the money you receive, more valuable than the money you spend. You give a lot, including your all. If you buy a candy bar from the vending machine, you are not a bad child to your family. If you get your winter coat, food, and textbooks from a collective fund, you are not a burden. You’re an investment, not a charity case.

Low income Columbians, you belong here. You can love your school and love your family; or, you can hate this school and love the prospect of changing the world that waits beyond it. You can be grateful and still acknowledge that without you, this institution crumbles, and with you, it trembles. Feel that pride. Sit down. Enjoy your meal.

Jane Walsh (she/her/hers) is a Junior at Columbia College and in the Film and Media Studies department. She is Co-President of Latenite Theatre, Treasurer for CUFP, Diversity and Outreach Chair for KCST and a board member with Memento Mori Stand Up. She also enjoys being a University Life Ambassador with the Welcome and the Inclusion and Belonging Initiative. She is the one who eats all the brownies at Ferris; that’s why they’re gone when you get there.