How Curiosity and a Strong Grandmother Brought an Engineer to Columbia

At the age of eight, Krisna J Panchal (SEAS ‘25), already knew how to change the faucet and remove the pipes below her kitchen sink to fix a leak. By the age of ten, she was learning how to make repairs on her family’s Toyota Camry, which was as old as she was. Whenever a problem required outside help from someone like a plumber, Krisna was always there to keep an eye on the situation.

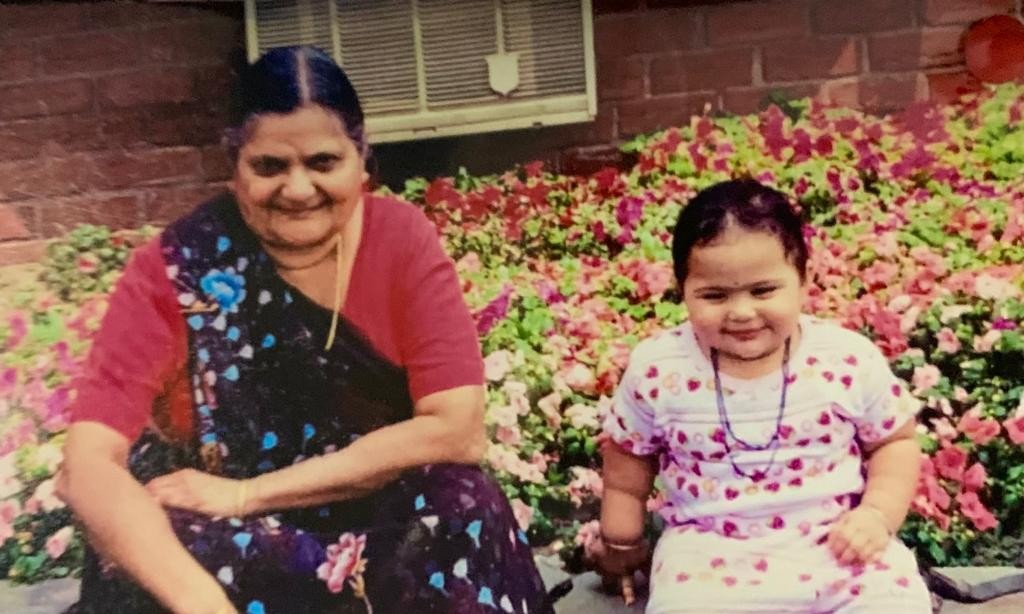

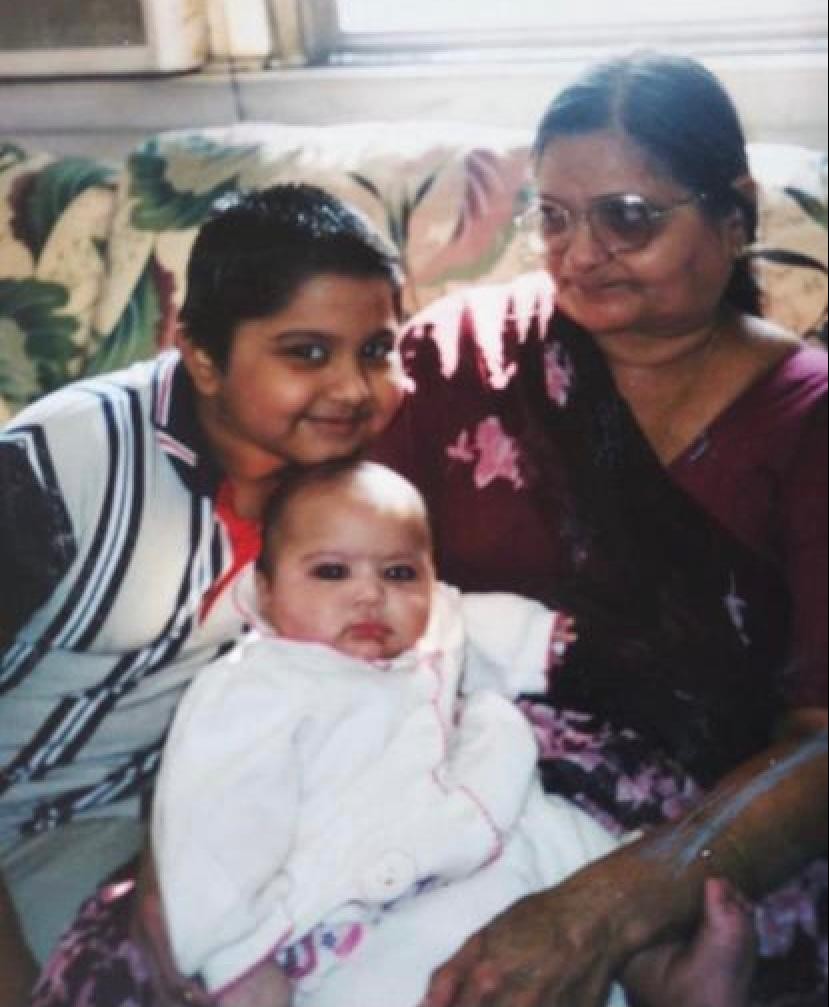

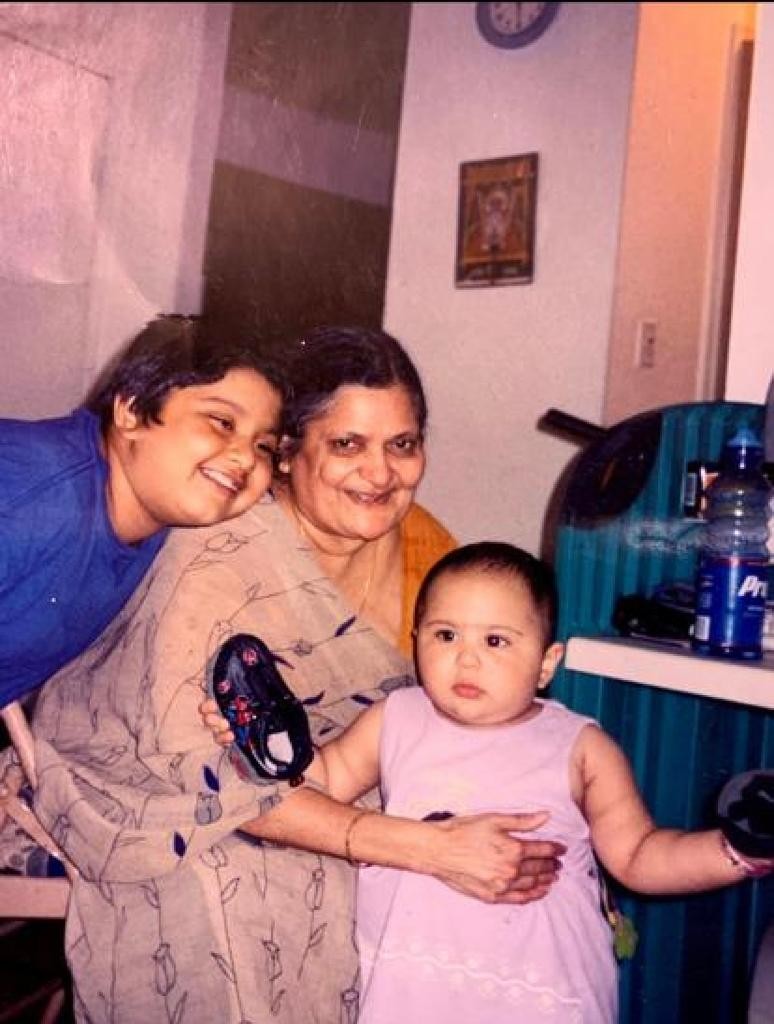

Krisna grew up with her father, an engineer, teaching her how to fix things around the house when they needed repair. But it was Krisna’s grandmother, Premila, who she says overcame many challenges throughout her life that would provide Krisna the opportunity to attend Columbia and become an engineer.

At the age of eight, Krisna J Panchal (SEAS ‘25), already knew how to change the faucet and remove the pipes below her kitchen sink to fix a leak. By the age of ten, she was learning how to make repairs on her family’s Toyota Camry, which was as old as she was. Whenever a problem required outside help from someone like a plumber, Krisna was always there to keep an eye on the situation.

“We would call someone and even when they came over to our house, I’d be like, ‘are they doing this right?’” Krisna jokingly said.

Krisna grew up with her father, an engineer, teaching her how to fix things around the house when they needed repair. But it was Krisna’s grandmother, Premila, who she says overcame many challenges throughout her life that would provide Krisna the opportunity to attend Columbia and become an engineer.

Krisna’s grandmother was born in an Indian village two years after the country had gained its independence from Great Britain and according to Krisna, her grandmother, and many women, were not permitted to attend school. Even if it had been allowed, her great grandparents did not have the resources to send Premila to school. Instead of getting the same education her brothers did, Krisna’s grandmother taught herself how to read and write at home, with limited resources.

Alongside her parents, Krisna’s grandmother immigrated to the U.S. at 60 years old. Her English was limited, but knew enough to pass the citizenship test. Krisna initially struggled with her own English at school, learning alongside her parents; but she performed well in areas like math. And thanks to an early morning routine from her grandmother, Krisna began learning English at a much faster pace.

“I distinctly remember she’d wake up and say, ‘you should watch something on TV,’ and I was like, ‘okay, I have no opposition to that,” Krisna said. “I speak better English than anyone in my family because of that. I kept watching different TV shows and eventually I would pick up on the English being used.”

Krisna’s English skills also improved through a different and unique route - defective books. Krisna’s mother worked as a production worker in a book bindery when Krisna was in elementary school. Anytime she would come across books with defects, she’d bring them home for Krisna–even if they weren’t meant for children her age. Krisna’s reading skills improved immensely, and on one occasion, Krisna brought in a fifth-grade textbook to her kindergarten class for her teacher to read aloud, and was surprised when the teacher told her it was too hard for the class.

“I was like, ‘What do you mean this is too hard?” Krisna told her teacher.

As a first-generation student from a low-income family, Krisna’s ability to learn English became increasingly important in helping her parents navigate life in a new country and overcome the challenges that come with a language barrier.

“My childhood was translating,” Krisna said. “My childhood was not playing around or whatnot. It was translating. It was paying bills. It was trying to find a job to help my parents. That’s what my childhood was. I want my [future] kids to not feel that. I want my generations after that to keep on improving and keep growing.”

But Krisna’s childhood also laid the foundation for her future in engineering. Her father had dropped out of high school but through experience, he became a mechanical engineer who never missed an opportunity to fix something around the house.

My childhood was not playing around or whatnot. It was translating. It was paying bills. It was trying to find a job to help my parents. That’s what my childhood was. I want my [future] kids to not feel that.

But Krisna’s childhood also laid the foundation for her future in engineering. Her father had dropped out of high school but through experience, he became a mechanical engineer who never missed an opportunity to fix something around the house.

“My dad always told me from the beginning, ‘if something goes wrong, you figure it out and fix it.’”

With a house located in a flood area, Krisna learned how to use, fix, and replace pumps. If the showerhead began to develop rust and needed cleaning, Krisna knew how to take it apart and either clean it or rebuild it with new parts. When it came to the family’s Toyota Camry, Krisna wasn’t allowed to work on parts like the engine until she was ten years old. But once that time came, her brother would show her how to fix something, and then let Krisna try it herself.

“With the lights of the car for example, my brother would do one and then give me the second one to do,” she said. “My dad taught my brother and then my brother taught me.”

Her experiences fixing lights, sinks, pipes, the family car, and helping her parents with logistical tasks fostered a love of engineering. Encouraged by her grandmother, Krisna pursued her passion and excelled in high school and in extracurricular activities like the robotics club.

But the idea of going to college was unfamiliar. Krisna says she participated in clubs and activities because she loved them; she did not realize that her participation could help her get into college. With no one in her family having ever attended college, Krisna wasn’t sure where she would go.

Through QuestBridge, a nonprofit that connects low-income and first-gen students with partner colleges and universities, Krisna learned about other potential options for college including Columbia and Princeton.

“QuestBridge was the first time I ever considered going to a school that was not a state school or community college,” Krisna said. “I never considered them because I thought, ‘these schools are for rich people.’”

Krisna applied to Columbia University in 2020 - and didn’t get matched. She applied to several other schools including Princeton but decided to try Columbia again through an early decision application. In typical pandemic fashion, she sat on a zoom call with three of her closest friends before finally seeing the life-changing decision she was waiting for.

“That night I tried sleeping after knowing I got into Columbia,” she said. “I literally could not sleep because I thought: this has been such a long journey to get here. Straight from my grandma not being able to even go to school, to me being able to go to one of the best schools.”

I literally could not sleep [the night after I got into Columbia] because I thought: 'this has been such a long journey to get here'. Straight from my grandma not being able to even go to school, to me being able to go to one of the best schools.

Outside of being an Ivy League school, Krisna wanted to attend Columbia because of the sizable and growing first-generation and low-income community. She says she fell in love with the engineering program because of their commitment to engineering for humanity.

Although she’s a first-year student at Columbia, Krisna plans on completing her biomedical degree and has ambitious post-graduate plans to travel to India and help build improved water and sewage systems in small villages. She says locals must travel far to access clean water and hygiene facilities.

“There’s so much infrastructure and engineering work that has to go into these villages,” she said. “That’s one of my goals in life. I want to go there and help, but I feel like I need the knowledge first.”

After overcoming challenges on her road to Columbia, Krisna says her experiences have led her to have a desire to continue to grow in different aspects of her life, and hopes others see that they can also grow.

“You’ve got to be the change that you want. I know it’s going to be hard. I’ve experienced it. I know what it feels like to not be able to go on school field trips because I can’t afford it. I know what it feels like to have people tell you, ‘you cannot do this,’ because of something irrelevant like your gender. I know what it feels like to shower in cold water because you can’t pay the heating bill. I know that a lot of people go through that and don’t really like to talk about it.

Now at Columbia and celebrating Women’s History Month, Krisna says she’s grateful for the sacrifices made by her grandmother that have allowed her to pursue a degree and be able to give back in the future.

She says she’s inspired and thinks of her grandmother everyday when she picks up a pen. In some parts of India, it is customary to only use your right hand because the left hand is associated with hygiene and being unclean. However, in learning how to read and write, Krisna’s grandmother used her left hand because that’s how she naturally wrote, and taught Krisna to do the same. One of many habits and memories she would thank her late grandmother for.

“It’d just be two words: Thank you. I’m so grateful for everything that she did. Grateful for the idea of her and her story. That has been with me since she died when I was six years old. It’s been 13 years of my life. Just pushing on and knowing her story. I would just like to thank her for going through all of those struggles so that I wouldn’t have to in the future.”

Krisna Panchal is a first-year student at The Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science (SEAS) and is pursuing a degree in biomedical engineering.